War Never Changes

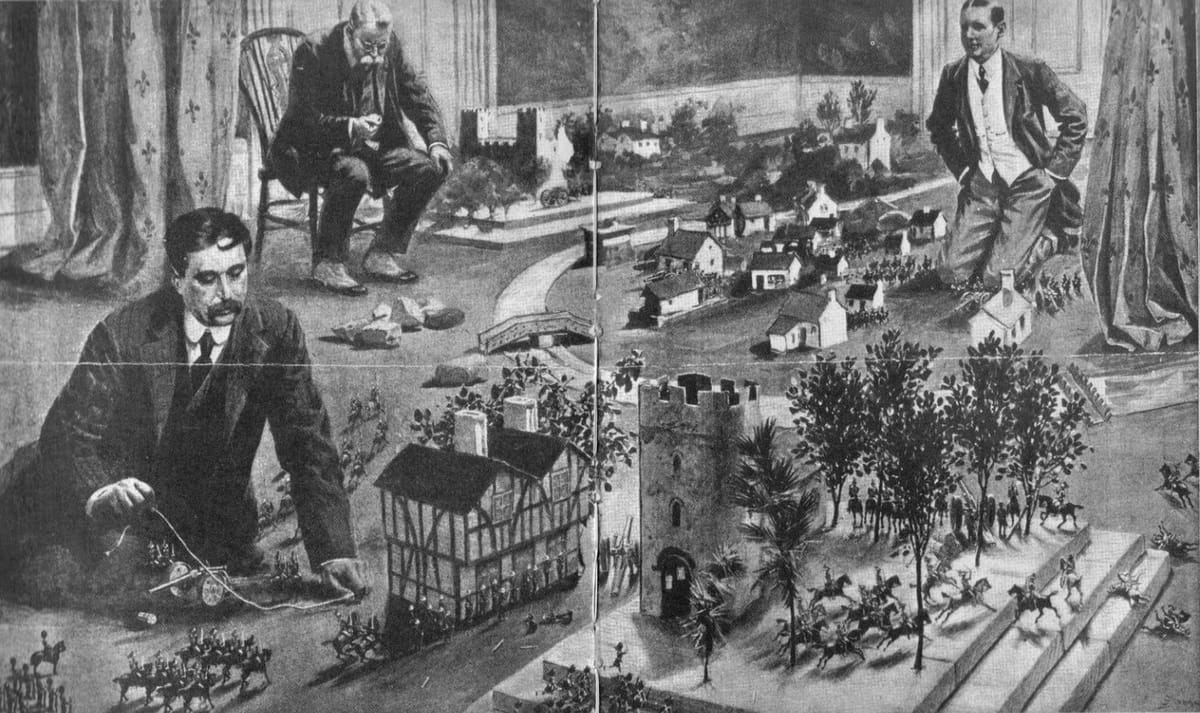

The matter of how best we play our own Little Wars around the game table has completed innumerable revolutions throughout the history of the hobby.

I have read with great interest the recent article by Gus L of All Dead Generations on his rules for Dungeon Skirmishing, and I wish to return my own small salvo of penetrating thoughts. The matter of how best we play our own Little Wars around the game table has completed innumerable revolutions throughout the history of the hobby. Let's quickly survey some high-level approaches.

Wargame

The indisputable roots of the hobby. Traditionally miniature figures or tokens are used to track military units (at individual or aggregate scale), moving around either free terrain with ruler or by grid cells. We live in a golden age with domestic 3D printing, and there is no shame in cardboard or dice tokens. We do not need heavy rulesets that take hours per conflict to resolve, and do not need production values like Critical Role. Look to RPG Savage Worlds or wargame family One Page Rules for how simple it can be.

There are undoubtedly many other adherents to theatre of the mind. This I argue is not fundamentally different, though interesting how I can't think of a wargame that eschews all physical representation as we are so want to do for roleplaying games. Gus' skirmish rules strike me as a somewhat convoluted way of addressing an issue that is more readily solved with figures or tokens (and is quite reminiscent of the combat rules from The One Ring).

Regardless of representation, this style of combat fundamentally allows either side to 'win' and any individual unit may be lost on the whims of fate. Induced play tends to focus on replicating small scale skirmish tactics: exploiting choke points, keeping an armoured front line, using spears from the second rank as a force multiplier, and keeping the artillery (magic user) in the rear. This is all reasonable, but arguably a bit one-note.

Contest

Games like Tunnels & Trolls, Mouse Guard/Torchbearer, and Agon frame combat as a contest occuring between sides rather than the atomic actions of each participant. This is a far less popular approach, but has some potential advantages to wargames. It is much simpler to adjudicate efforts for one side to flee or capture the other, and it tends to allow minimal real world time to resolve.

For adventure gaming that ascribes to the key pleasures of push your luck play balancing exploration, time, supply and threat (as Gus himself has argued) it crystallises the decisions of when to engage and for what purpose. It also marries with the goals of Decisive Combat and Information, Choice, Impact advocated by Chris McDowall. This seems to warrant more attention, especially amid the current interest in megadungeon play, where resolving the minutia of battles is time worst spent.

Drama

Games like Apocalypse World, Blades in the Dark and Jason Tocci's 2400 series present a rather different approach: violent action is fundamentally handled the same way as other risky actions. We focus more on the specific fictional details of how characters move and act upon each other, and often describe the action 'cinematically.' There is less emphasis on systems mastery, and we tend to favour narrative privledge or novelty in adjuducating the outcomes over adherence to more protocolised tactics.

I think this style gets a bad rap in modern traditional circles (such as much of D&D5E), but actually suits the needs of this play style better. We want to see our toys (characters) take on impressive foes and come out on top with action hero displays. The drive to use wargame procedures to try and emulate drama invokes the necessary evil of smoke and mirrors: tight player character and encounter balancing over advancing levels, and endless debates on resting & resource management - shadow boxing.

Puzzle

This seems intuitively a good fit for combat as war 'OSR' play, but needs some detailing. Wargames certainly present problems to each side, and many of the potential solutions may seem creative or essentially exploitative. Puzzle combat is really where some realisation or 'eureka' moment must occur. A nice example I saw recently was an early episode of the live action One Piece adaptation, fighting the clown pirate Buggy: no amount of slicing & dicing would overcome his special power to animate his separable body parts, but they trapped him in a set of chests to prevent re-constitution.

Many folk tales imply a puzzle approach to their antagonists: uncover their true name, wield a blade of silver, expose them to sunlight. This can be used as mere seasoning in other styles, or emphasised by establishing (like Cthulhu Dark and Trophy Dark) that you will lose with certainty if you fight monsters head on. An excellent example of this is Dreaming Dragonslayer's Skorne, where combat is diceless and you know perfectly which side will lose the race of attrition if you just bop each other, but it then frames the play around how to wrest the upper hand from your foe.

Game

A more abstract/'gamified' approach like the card-based abilities of Gloomhaven or (what I understand from a few blog posts) of the tarot card system of Rise Up Comus' His Majesty the Worm is important to highlight. There is a trend to shy away from dissociated mechanics like these, but especially if paired with a more high-level contest approach, has the distinct merit of facilitating the import of designs honed over decades in the board games scene.

Conclusion

It is critical that we ask (as in life, so in play): why do we fight? There is a somewhat perverse obsession with hit and damage dice, attack bonus progression, and reach and positioning on a 5ft grid (or abstractions like the ranks of Gus' motivating article) in 'OSR' circles that would otherwise rebuke the label of wargamer. If we aren't wargaming, put down the Combat Resolution and Weapons Versus Armour Tables, and start playing around with all these other tantalising morsels of fictive ultra-violence!